Currently based in Toronto, Cormorant Books began on a farm near Dunvegan in Eastern Ontario in 1986. The company was founded by Gary Geddes, who established a publishing company to give voice to diverse writers from across Canada. In 2001, Marc Côté became the publisher of Cormorant and continued the tradition of publishing first novels and short story collections from throughout Canada, adding more Québécois novels in translation and serious non-fiction to the list.

The books published by Cormorant and those published under the children’s literature imprint, DCB, have been nominated for hundreds of civic, regional, provincial, national, and international awards.

“I believe that good books in the hands of children, students, and adults make a difference.” Marc Côté, President and Publisher of Cormorant Books

Why I Publish with Marc Côté of Cormorant Books

What is Cormorant Books' story?

Cormorant Books was founded in 1986 by the poet, editor, and Concordia University professor, Gary Geddes. The reason Gary chose the name “cormorant” for his new press was because he believed the cormorant was a voiceless bird. (Not the case, it turns out.) The idea was that this new press would provide a vehicle for the voiceless, writers from the margins, whose work was not being published by the mainstream. For the first nine years, Cormorant published anthologies, poetry, translations from the Spanish, books by refugees, short stories, and novels. By 1995, Gary handed the press over to his wife, Jan Geddes, who focused more on first novels, short story collections, and translation of Québécois novels. Jan retired at the end of 2000, and I became publisher in January of the following year.

What kind of books does Cormorant Books publish?

We’re best known for literary fiction, especially first novels and collections of short stories. We also publish serious non-fiction, like Gwynne Dyer’s Shortest History of War, and Sandra Perron’s Out Standing in the Field, about Canada’s first female infantry officer, which will be released this autumn as a feature film. Our imprint for young readers, DCB, publishes quality fiction for young adult and middle grade readers, as well as illustrated children’s books.

How has Cormorant Books evolved since its inception?

The list has grown to include the occasional art book, biographies, serious non-fiction. We’ve added the imprint for young readers. Our staff is much larger. We’re based in Toronto, not a farm house in Dunvegan, Ontario.

What has the publishing journey been like for you?

Sailing on a large yacht in a storm. (I get sea sick on the ferry crossing to Toronto Island.)

Cormorant Books is a highly-regarded book publisher. How does Cormorant survive, and thrive, in such a competitive marketplace - there are only so many readers?

When I see the sales numbers for any number of books by Stephen King, Colleen Hoover, or James Patterson, I see that there are hundreds of thousands of readers we need to reach, so I disagree with your statement “there are only so many readers”. There are enough readers to support a home-grown industry.

“We have managed to survive through blood, sweat, and tears. A belief in our authors and their books that transcends the hundreds of small and large catastrophes that plague this industry.”

What is the current state of book publishing?

Not a lot better than the current state of politics in the US of A. Our trade market is dominated by foreign-owned publishers who take up booksellers’ budgets and shelf space. They crowd us out. They crowd us out in the limited legacy media still occasionally covering books.

What do you know now that you didn’t know at the beginning of your journey as publisher?

The joke “How do you make a small fortune in book publishing?” To which the answer is “Start with a large one.” Owning, in part or in whole, a book publishing company is a lot like owning a yacht; if you have to worry about money, you shouldn’t own one. I’ve spent twenty-five years worrying.

What has been your greatest challenge in publishing books?

Timing. There’s never enough time. The workload is heavy. There’s never enough capital. The grants aren’t sufficient. The marketplace is dominated by foreign-owned companies. Our libraries and schools still believe that they need to purchase foreign-authored and foreign-published books at the expense of supporting home-grown talent and businesses. I guess I was supposed to pick just one. But these, together, at the greatest challenges.

What has brought you the most joy in publishing?

Working with the authors on their manuscripts and achieving that “ah-ha” moment when everything falls into place. There is, however, a specific story. It’s how we came to publish Earth and High Heaven, the Governor General’s Literary Award-winning novel by Gwethalyn Graham, originally published in 1944.

In 2002, I received a request for a teacher’s guide to Lives of the Saints. The teacher was Marc LeBourdais. I asked him if he was related to Isabel LeBourdais, the author of The Trial of Steven Truscott. He was, it turned out, her grandson. We talked about how Steven Truscott had finally been released, so many years after the miscarriage of justice. Then I asked Marc a question. It was about his great-aunt, Gwethalyn Graham. Was he in contact with her son, or anyone directly related to the late author. “That would be Aunt Kitty,” he said. I provided Marc my contact information and asked him to ask his aunt if she would please contact me, as I wanted to re-issue Earth and High Heaven. An hour later, Kitty Graham called me.

But this isn’t the entire story. There’s much more.

When I was a student in 1981 at McGill, I took the twentieth century novel course, taught by Hugh MacLennan. (Hugh MacLennan was the five-time Governor General’s Literary Award-winning author of Two Solitudes and The Watch that Ends the Night.) There were no Canadian-authored books on the list of forty-two novels. So, just before the Christmas break, I asked Professor MacLennan why this was the case. “Because,” he said, “No Canadian-authored novels are good enough.” Somewhat taken aback, I asked, “Not even your own?” He smiled, “It would be unseemly to teach one’s own work.” Having made the first point of my argument, I asked the follow-up question, “So yours are the only Canadian novels worth teaching.” He paused and smiled, eyes twinkling. He knew what I was up to. “Of course not. I’d teach Earth and High Heaven, if it were still in print. Gwethalyn was a fine writer. The best of all of us.” I walked away from this exchange, making a mental note to check my mother’s bookshelves when I flew home to Vancouver. A few days later, I found my mother’s first edition of Earth and High Heaven. I took it back to Montreal with me, and read it on the plane. When I finished it, I promised myself that if ever I was in a position to make it happen, I would bring this novel back into print.

When, some twenty-one years later the opportunity presented itself, I did just that. On the publication date of the re-issue of Gwethalyn Graham’s novel, August 2003, the Toronto Star gave three pages to the event. Three pages. The front page of the Entertainment section, and a spread inside. Judy Stoffman, who was the books editor at the time, provided the readers of the Star with this book’s glorious history: it had topped the bestseller list of the New York Times for several weeks, with John Steinbeck’s East of Eden a few spots below.

The joy I experienced re-issuing this important – and very good – novel was profound. It remains profound. The novel is beautifully written, and is probably the finest example of social realism in Canadian fiction. It’s a book every Canadian should read, and should be familiar with. It should have been our To Kill a Mockingbird, taught in every high school in the country.

What have been some career highlights?

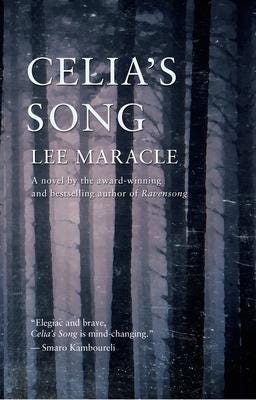

Standing in the room at the Four Seasons when Beyond Measure was named a finalist for the Giller Prize. Two years later, when Home Schooling and The Perfect Circle were named finalists for the same prize. When, more recently, Finding Edward was named a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award. When Firefly won the GGLA. Placing two books on the Globe and Mail bestseller lists at the same time: The Marrow Thieves in fiction and Claws of the Panda in non-fiction. Winning the Libris Award for small press publisher of the year – the first, second, and third times. Winning the Libris Award for Editor of the Year in 2008 and then again in 2009. When I had to call for a reprint of 7,000 copies of Charlie Pachter’s M is for Moose, two weeks after receiving the first print run of 7,000 copies. Working with so many authors on their first books, ensuring that their voices came through pitch-perfect. Working with Lee Maracle to bring out her novel, Celia’s Song, which was the basis for her nomination for the Neustadt Prize, the “American Nobel.”

What does success look like to you?

A healthy bank balance.

What are you most proud of?

There are so many moments, but if I have to choose just one: Listening to Cherie Dimaline’s acceptance speech for the GG for The Marrow Thieves being delivered by her friend, Susan, in Michif. When the speech was over, even the Chief Justice, Beverley McLachlin, had tears streaming down her cheeks. Hearing Michif spoken in Rideau Hall is something I’ll always remember and treasure.

Why do you publish?

I believe that good books in the hands of children, students, and adults make a difference. There are several studies that demonstrate the reading of fiction triggers empathy. (In one study, the control group read non-fiction. The control group did not experience the same increase in empathy.)

“Reading broadens our view of the world, allows us to step into the shoes of others, learn about things in-depth and at our own pace. A country with a strong publishing industry, publishing books of merit, has the potential to be a fully functioning democracy.”

About Marc Côté (in his own words):

Born in Ottawa in 1960. Moved to Québec City in 1963. Moved to Vancouver in 1967. Moved to Ottawa in 1971. Moved back to Vancouver in 1973. Grew up in an English-French speaking home for the first seven years. Attended junior high and senior high in a distant suburb of Vancouver, Lynn Valley. My locker was next to that of Bryan Adams in grade eight. Jason Priestly’s mother, Sharon Priestly, taught me English in grade ten. Attended Capilano College (as it was in the late 1970s) and McGill University. Was a student editor on The Capilano Review and at McGill was on the editorial and production team of Scrivener Magazine (where we were the first to publish the poetry of George Elliott Clarke) and wrote for the McGill Observer. Moved to Toronto, and worked for the Canadian Book Information Centre, the marketing arm of the Association of Canadian Publishers; Books in Canada; World’s Biggest Bookstore; the Ontario Arts Council; the Literary Press Group; Stoddart Publishing; the Canada Council; Dundurn Press; Cormorant Books.